Image (c) Shutterstock/Gabrel

By Jessica Knight,

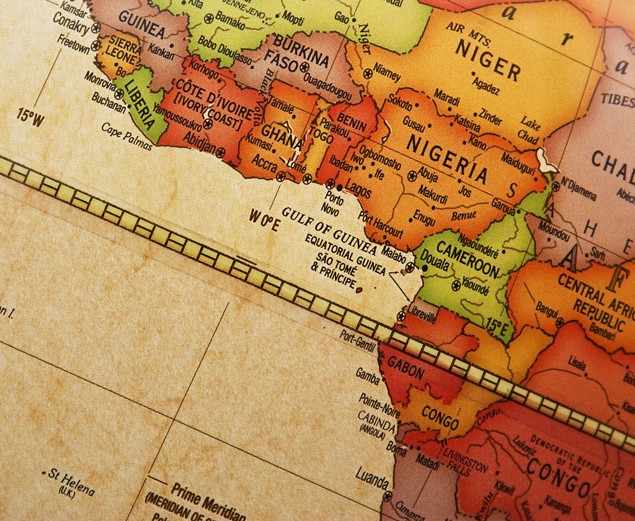

Nigeria and its coastal neighbors face a grave security problem in the form of rising maritime crime and militancy in the Gulf of Guinea – but there is no piracy in West Africa.

The word piracy has reentered the common vernacular as vivid and convenient shorthand for anything violent, criminal, or otherwise illicit that happens at sea. But piracy is not, in fact, a catchall term for maritime crime. It has a technical definition, outlined in Article 101 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS):

Piracy consists of any of the following acts:

- (a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed:

- on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

- against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State.1

The high seas here refers to international waters, which usually begin 12 nautical miles off the coast. But most of the maritime crime in the Gulf of Guinea today occurs much closer to shore. Every incident reported by the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) in the Gulf of Guinea since 2003 occurred well within the territorial waters or exclusive economic zone of Nigeria or its neighbors. As such, many of these incidents cannot be considered piracy under UNCLOS, our primary international convention on maritime rights and responsibilities.

But who cares about terminology? This is all semantics, right? Wrong. In the Nigerian case, here are three reasons why our words really do matter.

1. “Nigerian piracy” suggests false links with piracy in other locations, namely Somalia.

The resurgence of modern piracy in the last decade has centered on Somalia and the Gulf of Aden. From 2005-2010, Somalia alone witnessed 669 reported piracy attacks, with over 3200 taken hostage and nearly 50 casualties. This surge in the number and frequency of attacks included several high-profile incidents, such as the 2009 hijacking of the US-flagged MV Maersk Alabama. As a result, the piracy problem in Somalia captured significant public attention in international business, media, government – and even Hollywood.

Enter Nigeria. Attacks on vessels off the Nigerian coast increased 250% between 2006-2007 and continued to destabilize the region in the years that followed.2 Many observers viewed this rise of maritime crime in the Gulf of Guinea through the lens of recent experience in the Gulf of Aden. This heuristic proved more misleading than useful, and people failed to distinguish the two profoundly different phenomena. Piracy in the public lexicon became almost synonymous with Somali piracy – so much so that, on a few egregious occasions, the press reported activities of “Somali pirates in Nigeria,” seemingly unaware that the two countries lie on opposite coasts of a massive continent.

Analysts usually fall into subtler errors. The news is full of reports on the “shift” in piracy from East to West Africa, even from reputable outlets such as TIME and Foreign Policy. But the tempting language of trends, spreads, and shifts betrays a false assumption that pirate-like activities in East and West Africa are connected. True, piracy off the Somali coast declined sharply around the same time that certain types of maritime crime in the Gulf of Guinea began to rise – but nothing shifted from east to west. Piracy did not spread. Those developments have nothing in common, except both are happening in Africa and pertain to crime at sea.

Some great analysis has been done on this issue recently. Even so, the overwhelming tendency is still to speak as though Somalia and Nigeria are fighting a big pan-African piracy crisis, which simply does not exist.

2. “Nigerian piracy” confuses our thinking about possible responses.

The IMB just released statistics on Somali piracy in 2013, and they reveal a startling drop in activity: only 15 reported incidents last year, compared to 75 in 2012, and 237 in 2011. We can attribute this to a combination of increased shipboard countermeasures, to include wide-scale implementation of armed private security teams onboard vessels; a heavy international military response, including three multinational task forces policing the Gulf of Aden; and multiple UN Security Council Resolutions.

Such concerted international effort is not possible in Nigeria. All countries share responsibility for fighting piracy on the high seas, according to UNCLOS Article 100. But because most of the Nigerian attacks do not fit the UNCLOS definition of piracy, international law does not apply. The UN has no jurisdiction to send in a task force. Combatting violence in the Gulf of Guinea remains the legal responsibility of the coastal states, which have yet to demonstrate the capacity for effective response.

Even tactical counter-piracy measures largely depend on jurisdiction. In addition to hardening targets (e.g. using barbed wire on board ships), many shipping companies have begun to employ armed private security teams on vessels transiting high-risk waters. This has proven highly successful in the Gulf of Aden. However, Nigerian law forbids foreign armed security within its territory. Companies that wish to use armed security teams that have been vetted with international work histories must remain outside Nigerian waters. The alternative is to trust local navies and coast guards to provide protection, or to employ local Nigerian security teams with perhaps unknown work history, training, and standards.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the problem of piracy and maritime crime. We must recognize this in order to focus productively on addressing the dangers in the Gulf of Guinea.

3. “Nigerian piracy” obscures the real links between illicit activity on- and offshore.

Talking about Nigerian piracy not only builds false links to piracy elsewhere, but it also obscures the very real links to what happens onshore. Nigerian piracy does not occur in isolation. It is part of a system of illicit activity that spans the entire Niger Delta region and the Gulf of Guinea.

You see the same mix of actors on and offshore: impoverished youth with no legal employment opportunities, local criminal networks for bunkering and refining, organized militant groups with grievances against the government and international oil companies, corrupt officials stealing oil on an industrial scale. They engage in the same types of actions, with tactical adjustments for the maritime environment: violent attacks, infrastructure sabotage, kidnap and ransom, theft, bunkering. These dynamics do not change whether you look on land or at sea. The only meaningful difference between “Nigerian piracy” and “crime and militancy in the Niger Delta” is that one happens on the water.

Context is everything, especially when looking at complex problems. When we talk about piracy as though it is fundamentally different than illicit activity on land, we rip it out of context. We draw a great seam in our analysis right down the coastline, which leads to misinterpretation, information gaps, and flawed conclusions.

However, when one identifies piracy as part of a broader, systemic problem, new avenues for insight emerge. Suddenly, instead of an inexplicable rash of hijackings and kidnappings in the Gulf of Guinea, we see the extension of a deeply rooted, complex and ongoing conflict. The roots of the conflict are onshore. The effects are spilling over into the Gulf. When we situate piracy within this context, new trends and patterns appear, and the big picture becomes a little clearer.

What does this mean?

Despite these real concerns, the phrase Nigerian piracy is unlikely to vanish from public use. Nor should it! Maritime crime and militancy in the Gulf of Guinea may be more accurate, but it is certainly not more practical.

While we do not need to obsess over terminology, we need to remember that the words we use to discuss something can unconsciously shape our thinking about it – and not always for the better. Nigerian piracy is useful shorthand, but only if we all know what we’re really talking about.

About the Author

Jessica Knight is currently a second year Master’s student at Stanford University’s Ford Dorsey Program in International Policy Studies. She is also an acting Fellow Six Maritime LLC studying security and stability solutions in Nigeria.

1 UNCLOS elaborates on this definition in Articles 100, 102-107.

2 The 250% figure is according to self-reported IMB data, which must be taken as a conservative estimate. The actual rate of piracy is likely much higher.